zur herknerin

text: Julia Vitouch, photo: Olivia Wimmer

text: Julia Vitouch, photo: Olivia Wimmer

‘Installationen’ is the storefront name of one of Vienna’s most authentic restaurants… or so it appears. Concealed behind the large 1950’s lettering, ‘Zur Herknerin’ is a contemporary- take of an Austrian Wirtshaus. The restaurant owner and chef, Stefanie Herkner, shares her secrets on how she made her vision of a modern Viennese Wirtshaus come to life.

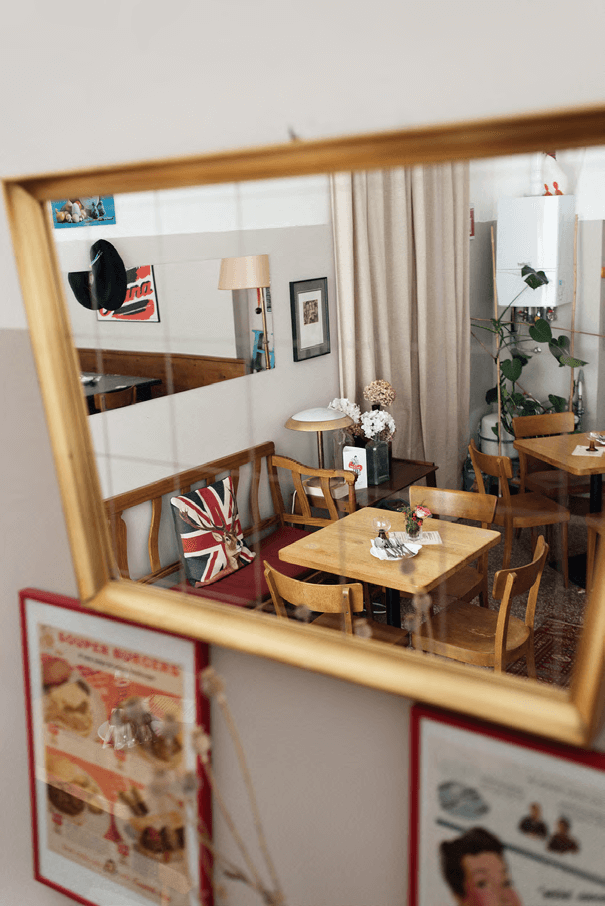

We meet to chat about her restaurant and as we sit down on a wooden bench, Stefanie tells me that it used to be in Thomas Bernhard’s country house. As I look around, I realise that every piece of vintage furniture, lamp, photograph and drawing was handpicked and arranged by Stefanie herself, and has–as she adds–it’s own history and emotional value. While we talk, the hustle didn’t stop. Although the Wirtshaus is still closed, Stefanie and I are interrupted continuously by colleagues, delivery guys and already by hungry guests. Stefanie laughs, while receiving a thank-you gift from a couple dropping by, “I hope you don’t mind, but it’s just never quiet around here!”

You opened your restaurant around six years ago with immediate success and without ever receiving a formal cooking education. When was the moment in your life in which you made this bold decision to go into gastronomy?

I was around 28 and I was working in an office job in London. I had studied cultural man- agement after having studied art history in Vienna. I was miserable and bored and finally, when I was back in Vienna, I called my mother and told her, “Mama, I’m going to open a restaurant!” She was totally against it at the start. Now, she is around everyday, helping and teaching me! This has become, besides good food and a wonderful but small team, my secret for survival.

Both your parents used to cook. Your father, Heinz Herkner, ran a very popular restaurant called ‘Zum Herkner’, that opened in the eighties. Critics claim that he was Vienna’s finest cook of his time, reintroducing authentic Viennese dishes into the menu. Why did your mother react that way to your decision, despite her background as a cook?

Well, my parents actually forbade me to get into gastronomy, but it’s true that it was both their professions. My mother met my father during her apprenticeship at his restaurant. I think they did it to protect me, since the job is very tough. It’s a lot of work! My father was an icon; Peter Alexander and all the VIPs of that era would eat there and push its popularity. That sure was helpful. I never questioned their advice, until it became clear that I didn’t want to end up in front of a computer.

How do you deal with such big role models? Did you incorporate their cooking style or seek some distance?

I absolutely and totally went back to the roots of my parent’s cooking and I am learning from my mother’s craft on a daily basis. When you grow up with two cooks, everything in your life is about cooking. Every trip we took was about food.

Where were the places you travelled to?

When I was about seven, we went to Northern Spain and met Paul Bocuse and later, Chef Candido. Back then, you didn’t have star cooks on every corner as things weren’t that cos- mopolitan – so those moments were really special. I was impressed by all the fuss they made about wine tasting and how they polished the cutlery, which was exclusively copper. Those memories – they stick.

Did you spend much time at your parents’ restaurant as a child?

Yes, when I had school break, I loved sitting in the kitchen to observe. It was a tiny kitchen, but five people were still working there and things had to move fast. I had a little wooden stool between the two stoves and I would sit there, following the hustle without moving, as the kitchen is a dangerous place. When everyone was outside and I was alone, I started to taste everything and peek into every pot.

Did you have a favourite dish or was there something special your parents prepared for you?

It was pretty simple and it still is the case (laughs. I love the side dishes of the Viennese kitchen. There is a photograph here on the wall of my father and his famous Kalbsbrust (fine stuffed breast of veal). I wasn’t interested in a big piece of juicy meat; I craved the bread-dumpling-stuffing that was streaked by the roast’s aroma or the Nockerl (spätzle-noo- dles) from the Paprikahuhn (paprika chicken), served alone with the thick paprika sauce. A good Grießnockerlsuppe (beef-broth with semolina dumpling) was and still is a pleasure to eat–so you see, already as a child, I worshiped the essence of the Viennese kitchen. They were simple, tasty homemade dishes.

How did you revive the essence of Viennese cooking here in your own restaurant?

Before I opened the restaurant, I was asking myself if there was a place in town where I could just go, sit and enjoy a plate of self-made beef broth. I honestly couldn’t figure that out, be- cause for me, there simply was no place with the right atmosphere, the down-to-earthness and sufficient quality of food. It became clear that I wanted to create exactly that–a place where the Viennese kitchen could thrive in. What Viennese kitchen really is, is regional, seasonal, fresh and a ‘home-made’ way of cooking.

And you don’t even need a Schnitzel on your menu! How strong really is the bond between meat dish-es and the Viennese kitchen?

I think that there are so many other great options and recipes! Take, for example, the Dill- fisolen (green beans with dill), Karfiol mit Brösel (cauliflower with buttered breadcrumbs), Linsen (lentils), or Rösti (hash browns). These are dishes that I try to enhance because they are tasty and easy to get. Whereas meat and fish that is regional and organic becomes increas- ingly difficult to get your hands on. We don’t serve Schnitzel, that’s true, but actually nobody misses it. I don’t even serve steak, because the Viennese kitchen isn’t a kitchen based on filets.

Traditional recipes teach us how to use all parts of the animal. Do people still order dishes contain-ing innards like lungs or tripe?

Less than in my father’s time, but they still do. When it comes to meat, currently I have Fas- chierter Braten (meat loaf) on the menu and I serve Sarma (Serbian stuffed cabbage). The Sarma shows how international the Viennese kitchen is. It’s a kitchen of the crown lands, where a lot of influences come together and what subsequently makes people come togeth- er. Sarma was a key dish from the beginning.

Just like your dumplings?

Exactly, they are even on my logo, in front of my chest and steaming! (Laughs)

You teach people how to make them at your Dumpling Academy. Do you enjoy passing on your knowledge?

Totally, I could do much more seminars; I just don’t have enough time for everything! When I started cooking, my mother told me that it took her 30 years to master dumpling making. I was shocked as that was way too long for me! I realised that the instructions in cooking books are usually quite complicated. I engaged in the task and really tried to break it down to a simple but effective procedure and started showing it to people. I would cook three types of dumplings in a row together with them. After that, they usually have a good base to work with and can start making dumplings at home. Because once you get it, you’ll see what a ‘multi-talent’ the dumpling is, that can complement many dishes or just stand for itself, like in an apricot or plum dumpling.

One side of my family holds the belief that traditional Marillenknödel (apricot dumplings) are made out of potato dough, the other side is for curd cheese. Which side would you be on?

I must admit, I make the dough from curd cheese–but I love such discussions! How wonder- ful is it that every family has it’s own approach and that people still debate about that stuff. In times when everyone just stares at his or her phones, such conversations are rare and that’s why I think we need to cherish them. Because you know, it’s about something real!

I totally agree. Your dishes seem to be living memories, treasures from one’s childhood and forgotten knowledge brought back into our daily lives. You seem to have a modest approach that puts the food itself into the centre of attention. Would you agree with that?

I do, because I never had the urge to invent something new… you know? Gastronomy is so male dominated and they all seem to have the need to reinvent the wheel. I never wanted to present my personality on the plate. For me, the guests and his/her feelings when smelling the food, eating it and the food itself, are way more important. The Viennese kitchen is a very feminine kitchen because it was always the grandmother or the mother who would cook – on farms, in the city and in the small kitchens of their homes.

Error: Contact form not found.